Darkness started to fall and the street lamps flickered on, casting a warm hue over the damp cobbles. The smell of rain lingering in the air, mixing with hints of mulled wine and cinnamon. I walked through the door and felt the heat hit me, my bobble hat and scarf off in an instant. I started roaming the aisles and was drawn to a particular cover and title on the top shelf, just in reach of my lanky, bony teenage arms.

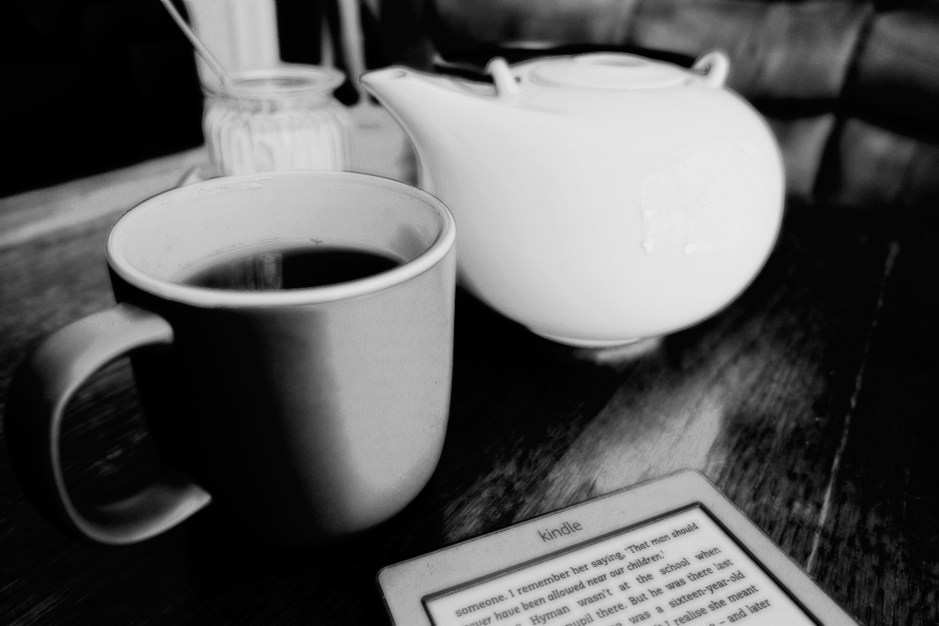

This is my first memory of going book shopping as a teenager. I can remember it vividly. I was out shopping in Norwich just before Christmas, with the early nights drawing in. I had stepped into my favourite bookstore – back before Ottakar’s was taken over by Waterstones. My dad would sit upstairs in the coffee shop – before it too was taken over by Costa Coffee(!) and enjoy a latte whilst reading a book. That was the beauty of Ottakar’s. You could enjoy a novel over a cuppa before you bought it – nobody was sat there worrying about spilling coffee on the pages.

The book was in the main section of the store on the top shelf, in the area where both well-known and up-and-coming authors are displayed. It had a simple cover, but I was drawn to it. My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult. This was years before the film with Cameron Diaz and before Jodi Picoult was really famous. I remember being intrigued by the story – full of conflict whilst all the while dealing with a deeply moral issue. I’ve ready many books covering everything from a standard murder thriller to those about troubling issues like domestic violence and abuse. I recall reading Danielle Steele’s The Long Road Home at the age of 11 which, with hindsight, probably wasn’t appropriate. That remains one of my favourite books to date though.

So I thought it was only fitting for my first review to be a Jodi Picoult novel. Its one I initially read over 10 years ago and lent to a friend, but I never got it back. Recently I felt the urge to read it again so downloaded it on my kindle. It brought back memories of kicking back on my multi-coloured bedspread as a college student, reading late into the night until my eyes strained. The plot I could associate my teenage self with; a bit of angst and the apprehension of approaching adulthood.

The Pact

A no-nonsense title that explains exactly what this book is about. Set in North America on the Eastern Coast, two teenagers are raised from birth by parents who are best friends. The story focuses on their bond, developing from friendship to love and the pressure of trying to meet their parents’, their own, and most importantly the other’s ideal of ‘perfection’. From the beginning the reader is aware that the young girl has died, a supposed suicide pact. The story then weaves through time, bringing together the two sides of the story. The flip side of the same coin. The story is primarily told from the boyfriend’s viewpoint, Chris, who is standing trial for murder. Occasionally there is the the odd recollection from the girlfriend, Emily, but this is more for explanatory reasons to help further the plot. Without Emily’s occasional input the reader would be unaware of the reason behind her desire to die; the mis-conception that having been abused as a child would make her dirty and unsuitable as a girlfriend or future wife.

Picoult’s notorious writing style – switching back and forth between then and now – really makes this story come alive. Whilst subconsciously leading the reader to question the lovers’ devotion to each other throughout, the characters tell a different story – portraying Chris and Emily’s relationship as one of closeness, desire and inevitability. A natural progression from childhood, but perhaps unwanted. And that is one of my major bug-bears about this novel.

The few, infrequent passages from Emily do not go far enough to give her depth as a character. The reader views Emily as a delicate flower, beautiful and brilliant but introverted. She is a typical teenager in many senses; worried about schoolwork and wanting to see her boyfriend as much as possible. But her dark secret is not explored; in fact, it is almost minimised. The abuse is introduced so late into the book and skirted over so quickly – perhaps that is Picoult demonstrating how a victim of abuse may recollect it, by wanting to get it out of their head as soon as possible – that it does not do the story justice. Emily doesn’t feed on the abuse; it is not all-consuming of her and the sudden desire to kill herself seems to take a large leap from the abuse 8 years prior. There is but the odd sentence of Emily reviewing her abuse, but far more about how she viewed her relationship with Chris as platonic, relishing the closeness but deeply anxious about the sexual encounters that are a natural part of any adult relationship.

Emily’s desire to die is the crux of the story, but her reason is completely unknown to the other characters. In the absence of any emotional exploration of the abuse, the reader is left to feel like Emily is selfish, focusing on her own wants and not thinking about the effect her actions have on other people, most notably Chris and her parents.

Chris is far more reliable and believable as a character. I felt as a female reader that I connected with him far more than Emily. His routine and teenage musings were normal and mundane and he struggled to deal with the expectations of his strict father. His life, like many other young adults, was unremarkable in many ways. Except his deep insatiable love for Emily, which in my humble opinion, has been confused with lust.

The mothers of Emily and Chris take the next two starring roles, and they are as alike as they are different. Chris’ mother is like the wind; she has an appetite for life that rolls through the story combining passion with motherhood and the desire to do right by her son. Her early recollections of Chris and Emily during their childhood are the building blocks for the reader; understanding how the characters are so entwined and the inseparable lives they have led. Emily’s mother, Melanie, is quiet and subdued, an anxious speck of a woman in my mind. Whilst Picoult demonstrates the grief Melanie would understandably be feeling at the death of a daughter, it is viewed from a third person, a stranger looking in, detached. Her actions in the months following Emily’s death are somewhat textbook, but neither her sadness nor her anger are given the weight they deserve. I can only recall feeling true empathy for Melanie when Picolut depicts her visting her daughter’s grave on Christmas Day, saying it is Emily’s ‘first Christmas away from home’, as if she had gone to universtiy and would be coming home one day.

The emotion that this story stirs within a reader is quite one-sided. You are rooting for Chris from the outset, hoping against hope that he will be found not-guilty whilst all along suspecting that, if you were a member of the jury, you would probably find him guilty as charged. I found myself sympathising with Chris, even though a couple of things he said and did to Emily I would not have tolerated myself. Its that balance to his character that gives him depth; after all, we are all capable of doing good and bad things.

This tale is not one of forbidden love, but expected love. Expected by the parents, but also by Chris. Picoult explores love from many angles. She winds around the passion and familiarity Chris’ parents feel for each other and contrasts it with the restrained but restless love Emily’s parents have. Both sets of parents exude a protectiveness over Chris and Emily that is admirable and raw. I felt myself smile when the parents first became aware that Chris and Emily had shared a kiss as young teenagers; you could feel their joy in thinking that the families would be inextricably linked in the future by marriage, what they had hoped from day 1. In my view, it is the parents’ overwhelming love for their child that the reader benefits from most. The lengths the parents will go to, in their own ways, to do what is right by their child, no matter what.

Picoult is an expert at tackling controversial issues, such as teen suicide. She thoroughly researches the subject matter, the investigatory procedure and the legal process in a lot of detail and meets with various other professionals to bring the story together and give it life. However, whilst well researched according to the appendices, I do not consider the emotional aspect has been sufficiently addressed as what the story makes for in a good read, it lacks in the emotional make-up from very key characters. Both Emily and Melanie could be more developed, they are, after all, the ones facing the emotional uncertainty. The story is written from Chris’ point of view, as the victim of a wrongful accusation. But it is Emily who has suffered and Emily who is dead. Her family are the ones who would be living with that loss for the rest of their lives, whilst Chris could move on. It feels distinctly flat in that sense, uncharted territory that is in desperate need of being scouted out.

The novel is undoubtedly built around the concept of Love in all of its different forms. Yet there is one other lingering feeling; it pulls the reader through the novel, sitting in your subconscious until you acknowledge it like an old friend when you eventually turn the last page. Fate. Of all the characters in the book, none are in control of their lives. And the more, perhaps surprising, realisation is that Picoult seems to promote this within her work. Her choice of words infuse the characters with spontaneity yet acceptance of what is happening to them. Sure, the story needs to be told, but there is no open challenging of the situation each character finds themselves in; no struggle nor conflict within themselves.

About

Suicide is the cause of 0.1% of all deaths in the UK (as at 2015), with female suicide rates at the highest in a decade. Yet the suicide rate for males is 3 times higher than for females, with the age group 44-59 having the highest rate. The suicide rate for under 30 year olds remains the lowest, but is gradually increasing over the years. Unfortunately, the ONS does not break the age groups down into those pre-adult hood, but it is widely acknowledged that teen suicide is an increasing problem.

If you know someone who you think may be suicidal, encourage them to speak to the Samaritans and seek as much help as possible.